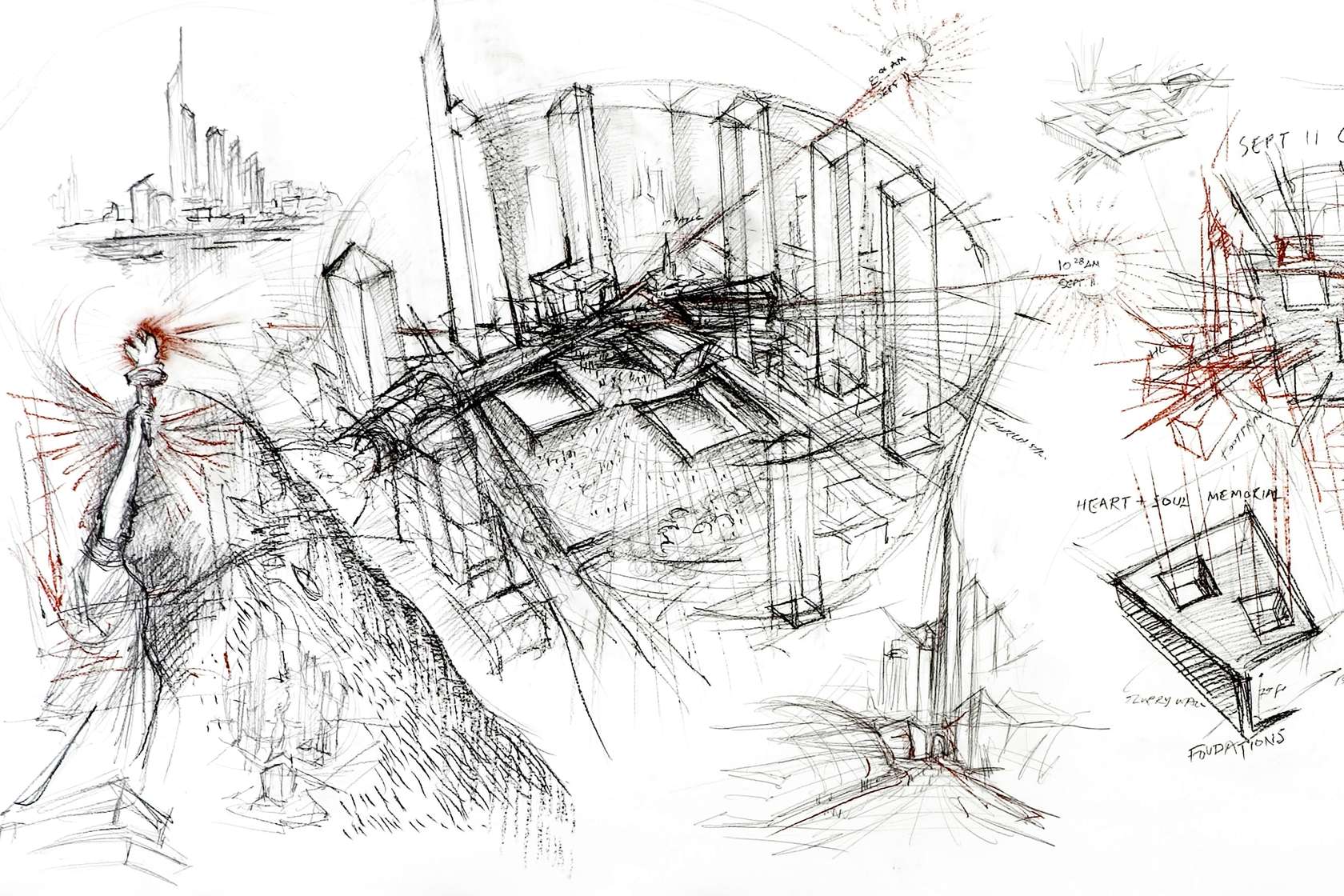

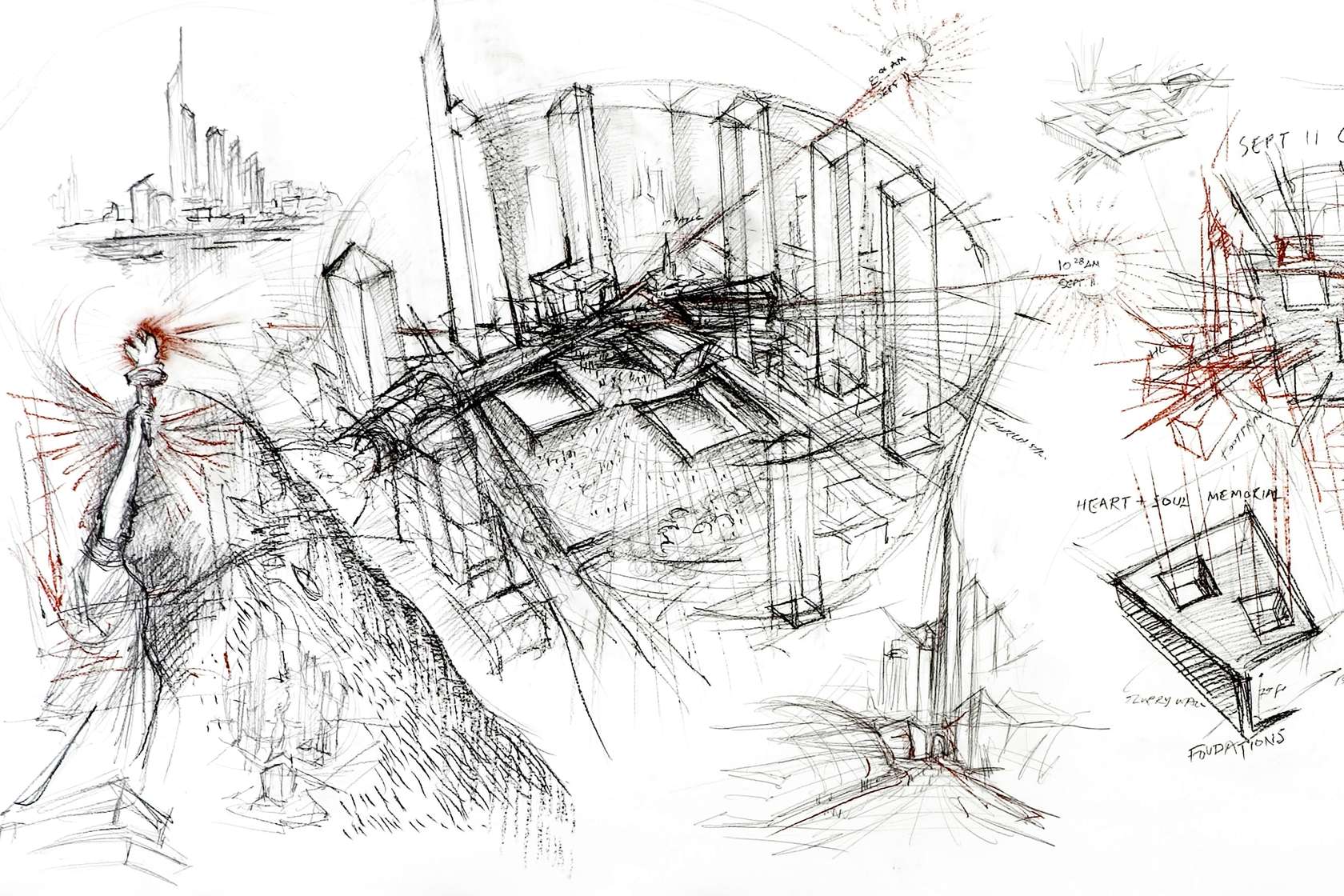

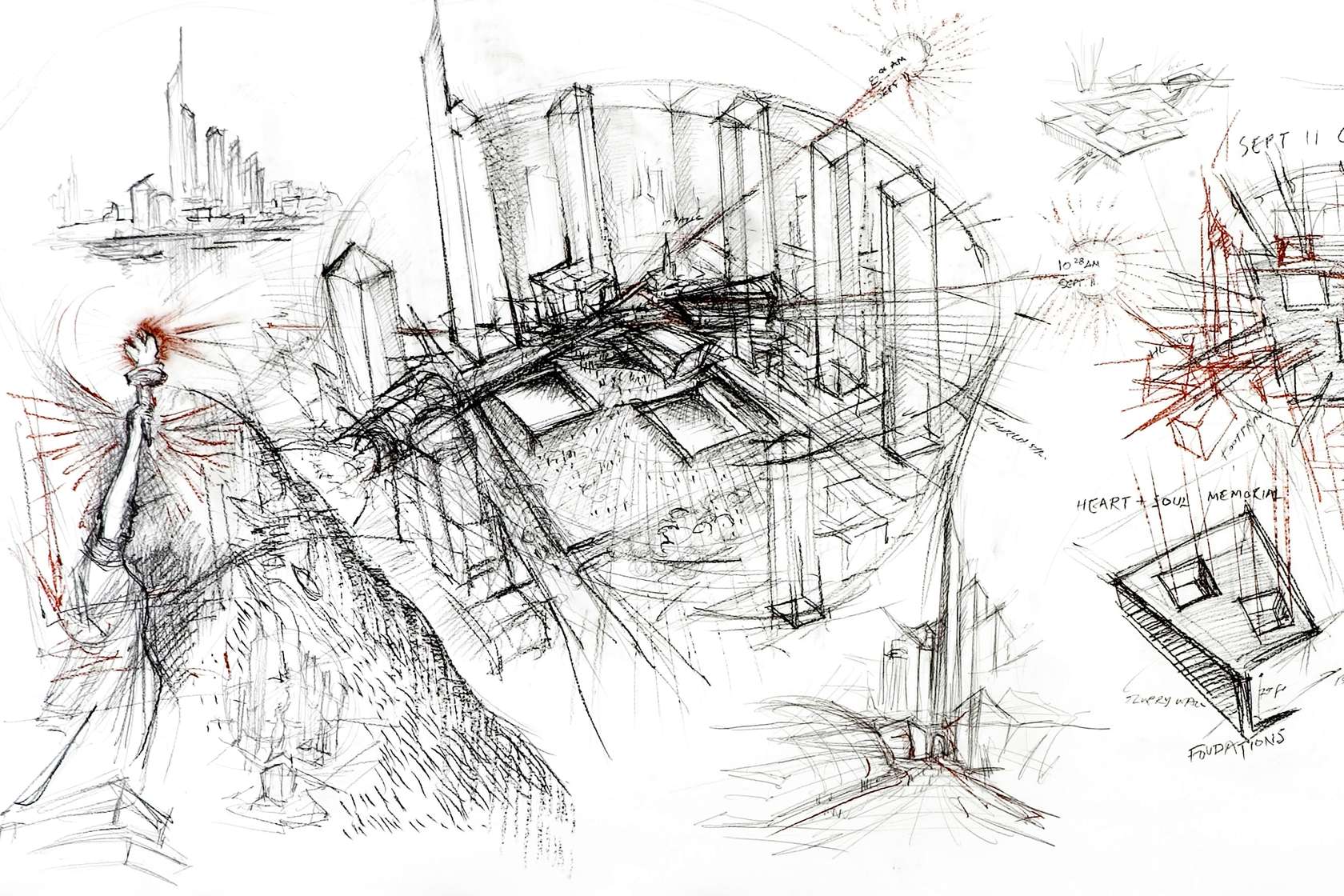

When looking through the drawing sets of most architects, you will find tools associated with precision: mechanical pencils with wafer-thin graphite tips, razor-sharp steel rulers and French curves for those ornate details. Sometimes, though, the creative spark for a project emerges with the use of mediums that are inherently inaccurate. Whether from the free-flowing lines of a charcoal stick or the thick strokes of a marker pen, the initial sketch frequently captures the visceral power of architecture better than a blueprint ever could. Daniel Libeskind’s sketch for the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada So the story goes, Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind was eating dinner in a restaurant when he sketched a design for the Royal Ontario Museum on a paper napkin. This impromptu burst of creativity culminated in the iconic Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, and the sketch in question is characteristic of Libeskind’s lose, expressive style at the initial stages of a project. Using any medium available to him at the time, Libeskind’s first design drawings are less about a building’s physical form and more about the story he is aiming to tell: the poetic narrative expressed through line and shade is key to the architect’s process, ... , Paul Keskeys, read more Architizer http://ift.tt/1UMT6v8

Yorumlar

Yorum Gönder