8 Renderings That Changed Architecture

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

Architectural visualization technology has undergone a rapid ascension, playing an increasingly critical role in the art of communicating architecture. Specifically, the process of 3D rendering — behind the incredible photorealistic scenes that are now so common within architecture — has roots dating back to the 60s. Half a century later, we thrilled to announce the launch of our exciting new competition, the One Rendering Challenge, which offers you the chance to win $2,500 and global recognition with a single rendering! Click the button below to register for updates:

Register for the One Rendering Challenge

Aside from the realms of architecture, design, and engineering, 3D rendering is equally pertinent in the world of animation. Advancements in CG technology impacts both industries, and it is fascinating to see how these two seemingly disparate worlds so greatly overlap.

If you’re looking for inspiration for your submissions to this year’s One Rendering Challenge or are simply interested in learning more about the lineage of architectural visualization, here’s a collection of some of the most influential and noteworthy renderings in recent history. While they are not all architectural in nature, they have all had a lasting impact on the architectural visualization in one way or another.

First, let’s rewind to 1968…

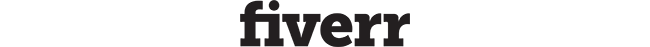

Assembled and exploded 3D rendered Soma Cube; images via firstrendering.com

The Soma Cube

Gordon Romney, the first computer graphics Ph.D. student, developed the first complex object ever rendered in 1968 at the University of Utah. It is a rendering of the Soma Cube, a mechanical puzzle invented by Piet Hein in 1933. Linear algebra operations of translations and rotations were specified to position the assembled object as desired.

The rendering program was initiated by light-pen to generate respectively the red, blue, and green scans to produce the rendered color image of the cube. Romney’s work showcased technology that would ultimately be commonplace in the design and presentation of architectural proposals.

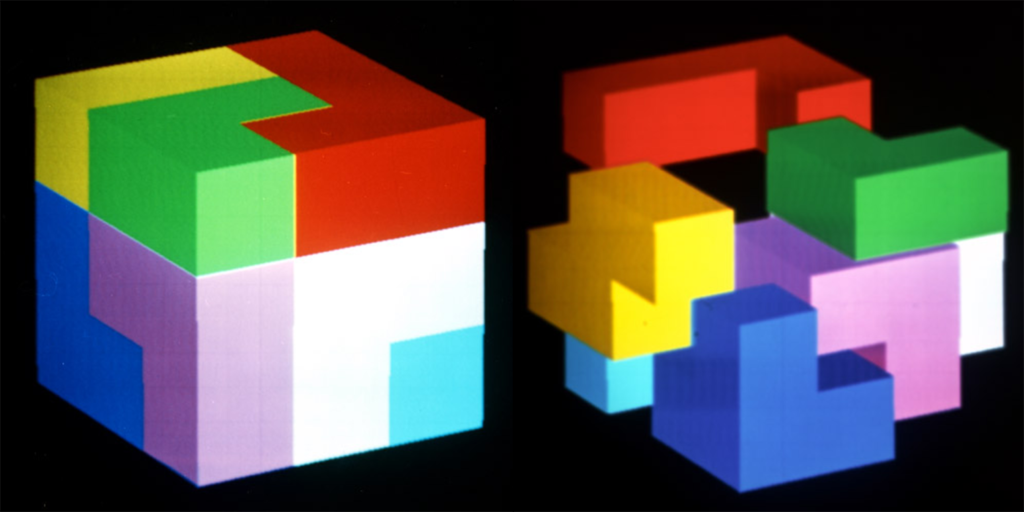

The teapot rendered as plain, shiny, patterned, and both; image via the Association for Computing Machinery, Inc., 1976

The Utah Teapot

The “Utah teapot”, created by computer scientist Martin Newell while a Ph.D. student at the University of Utah, is an iconic figure in the world of computer graphics. The teapot was developed to provide a complex form for simulating complex effects like shadows, reflective textures, or rotations that reveal obscured surfaces. The curves, handle, lid, and spout make it an ideal subject for experimentation as, for example, it can cast a shadow on itself in several places.

The teapot subsequently became a beloved test bed in the CG community. It’s a built-in shape in many 3D graphics software packages and has appeared as an “easter egg” in programs, such as Toy Story and The Simpsons. The “Utah teapot” is an early example of a process that would later become ubiquitous in architectural visualizations.

Frank O. Gehry & Associates, Inc. Lewis Residence, Lyndhurst, Ohio: Fish, Geometrical frame of the conservatory from Catia 3D model, 1989-1995; image via Gehry Partners, LLP.

Frank O. Gehry & Associates, Inc. Lewis Residence, Lyndhurst, Ohio: Elevation rendering from Catia 3D model, 1989-1995; image via Gehry Partners, LLP.

Catia 3D Model

From 1989 to 1995, Frank Gehry worked on the Lewis Residence, a laboratory for experimenting with new 3D modeling technologies. The technical drafts produced by the project allowed for new technology, materials, and techniques to emerge. The project also led to the development of a new, complex language of design, which was due in large part through the use of the Computer Aided Three-dimensional Interactive Application program, or CATIA.

A new generation of smart, digital design in architecture was born by using software to optimize designs and translate them directly into a process of fabrication and construction. Breakthroughs like this spawned terms that are now common in the architectural profession, such as parametric design and building information modeling (BIM).

Cornerstone

Tom Hudson, a co-creator of the 3D modeling and animation package 3D studio, created this animated short entitled Cornerstone using 3D Studio software. It was made to promote the 1990 launch of 3D Studio, the first iteration of the incredibly popular 3D modeling software now known as Autodesk 3ds Max. The story revolves around a building’s cornerstone dreaming of getting out and going to the beach.

The Third & The Seventh

10 years ago, Alex Roman’s short film The Third & The Seventh raised the bar for visualization. The CG animated film combines elements of architecture and film, and was created with Autodesk 3ds Max, V-ray, and Adobe AfterEffects and Premiere.

It takes us on a visual journey through many iconic buildings, including Louis Kahn’s Exeter Library and Tadao Ando’s Shiba Ryotaro Memorial Museum. Each frame of the film is beautifully composed; Roman’s use of light, camera movement and photorealistic CG sets a narrative that is surreal yet simultaneously authentic. He explores almost every environmental setting in the film, which continues to be a great source of inspiration for rendering artists around the world.

The concept design of Hadid’s Wangjing Soho; image via Zaha Hadid Architects

They copycat design; image via Der Spiegel

Wangjing Soho Complex and Meiquan 22nd Century

While Zaha Hadid’s Wangjing Soho complex was being constructed in Beijing, its doppelgänger, Meiquan 22nd Century, was simultaneously being built in the southwestern Chinese city of Chongqing. According to Spiegel Online, it is believed that digital files or renderings for Hadid’s complex, consisting of three pebble-shaped volumes, were pirated. The replica was actually being constructed at a faster rate than the original.

Plagiarism in architecture is nothing new, but the clarity with which the similarity was highlighted by these renderings brought the issue to the forefront of public debate.

Tianjin Citadel; image via BIG

MIR Rendering of Tianjin Citadel

Visualization studio, MIR, subsequently known for the “MIR style”, create scenes dominated by rich atmosphere and expressive natural settings. They embrace context and harness unexpected qualities inherent within architecture and its site to create distinctive, evocative images.

The above image of the proposed Tianjin Citadel by BIG is incredibly minimal, giving barely a hint of architectural detail. Contrasting with the hyper-sharp renderings we usually see, MIR leans heavily on atmospheric conditions to communicate the project. It establishes a specific tone and mood that highlights the character of the structure. Until recently, it was unconventional for firms to opt for such an understated rendering style, but the power of this approach is now being adopted by many big name practices globally.

“The Farmhouse” by Studio Precht

The Farmhouse

Studio Precht showed how compelling it can be to combine renderings with the aesthetic quality of traditional, physical architectural models. This is for “The Farmhouse”, a modular system that combines living and farming. It seeks to bring agriculture back into cities and back into the minds of consumers.

By making the production of food visible again, we can mitigate the harmful impacts current practices have on human and environmental health. The animation above is the most popular in the history of Architizer’s Instagram account, with 60,000 likes and counting! This popularity is a testament to the power of contemporary renderings to capture the imagination of a global audience.

Now it’s your turn — submit your most powerful architectural renderings for a chance of winning $2,500 and receiving global recognition for your work:

Register for the One Rendering Challenge

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

The post 8 Renderings That Changed Architecture appeared first on Journal.

, Nathaniel Bahadursingh, read more Journal http://bit.ly/2Wi9ZDJ

Yorumlar

Yorum Gönder